In kelp gone by

How looking to the past can help the future of seaweed forests

Carting seaweed for kelp on the Antrim coast in 1926. © W.A. Green, National Museums NI, Ulster Folk Museum Collection

We humans have a great affinity with the ocean. Across the globe, we have depended on marine and coastal ecosystems for millennia. So much so, that our exploration of these valuable systems has been at the forefront of global societal growth, security, and important cultural transitions.

Main photo: © W.A. Green, National Museums NI, Ulster Folk Museum Collection

Before we started monitoring the ocean, we were exploring and exploiting it for food, materials, navigation and well-being. This dependence looks different today, but it remains. It has not come without consequence either—as our reliance on the ocean progressed, so did our impact.

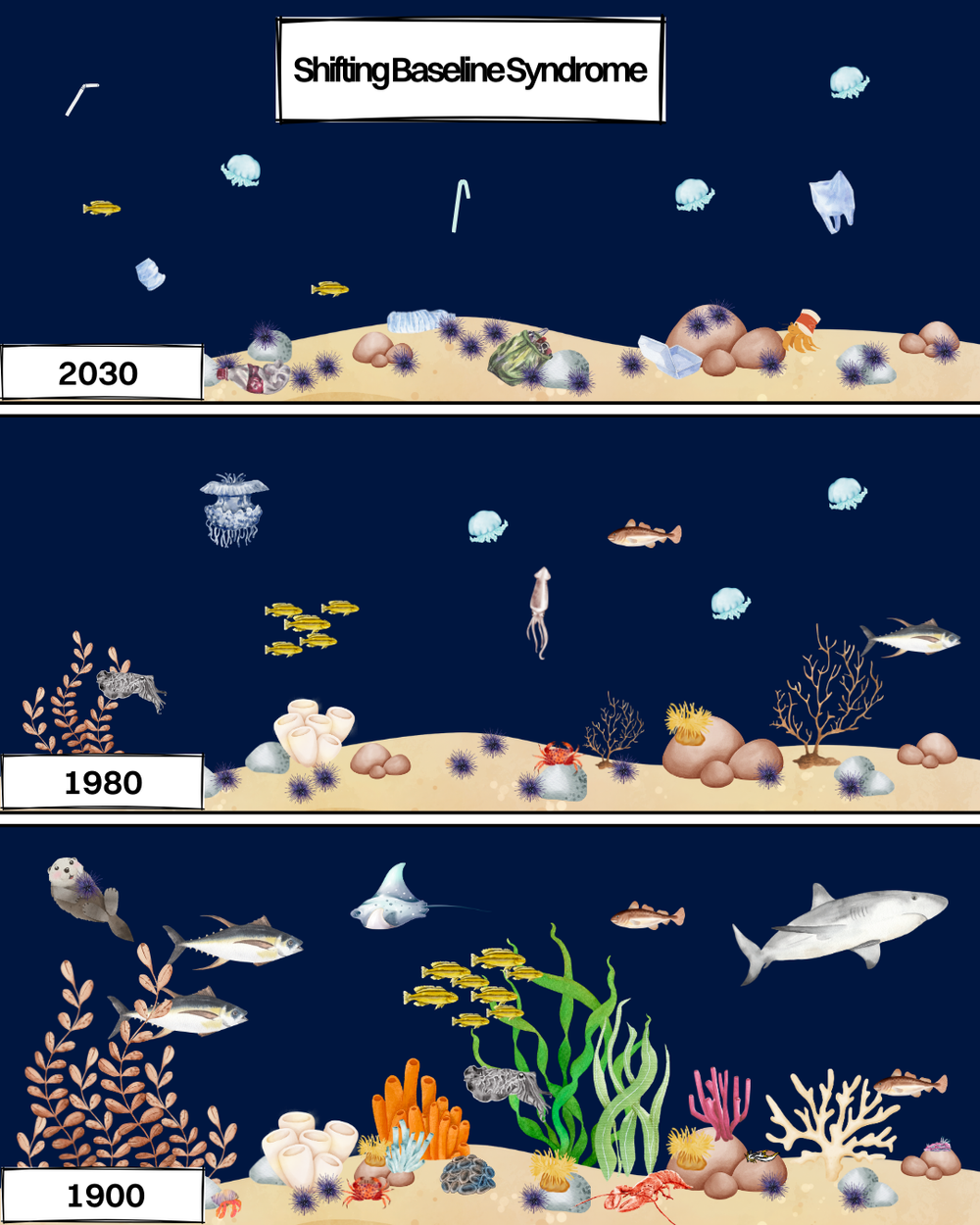

Today, we experience life in the ocean as a fragment of what once was. With our stories lost in time and our knowledge limited, we experience the ocean as our own—often new, yet diminished, normal (Pauly, 1995). Over time, our ‘normal’ shifts with ecosystem change, readjusted across individuals and generations, ultimately masking the true extent of loss (Pauly, 1995; Rodrigues et al., 2019; Thurstan et al., 2015). This continuous shift in perspective, known as the shifting baseline syndrome (Pauly, 1995), is perpetuated by the lack of long-term data on marine systems, given that our interactions with these environments originated long before we started monitoring them (Lotze and McClenachan, 2013).

Today, we experience life in the ocean as a fragment of what once was.

An example of shifting baselines can be seen in fishing communities located in the Gulf of California. A study by Sàenz-Arroyo et al., (2005) that documented historical fishing accounts with different generations of fishers, identified long-term changes in the marine environment that had been masked by inter-generational shifts in fisher perceptions. Compared to that of younger fishers, older fishers mentioned more species that were historically abundant, but are now depleted. Younger fishers were unaware of some species that were once common within their fishing grounds.

Knowledge gaps and rapid shifts like these allow the ocean’s history, and the extent of its change, to go unnoticed, and continue to be tolerated. The recent emergence of marine historical ecology—a field of interdisciplinary research that aims to bridge the gap and integrate historical sources into modern research—can change that.

Kelp forest communities of UK coasts.

Our evolving relationship with the ocean has revealed an unwavering reliance on its resources, providing global goods and services for thousands of years. Kelp forests are one of those resources—a group of large brown seaweeds, primarily belonging to the order Laminariales, kelps have proven their enduring value. Across the British Isles, kelps have been used for centuries. They were invaluable in progressing and shaping early industry, particularly in Scotland, where kelp was collected, dried and then burnt (a process known as ‘kelping’), to produce soda ash for glass and soap making. Later, a similar process was used for the production of iodine, providing a much needed substitute whilst all imports of Spanish barilla soda were halted during the Napoleonic wars (Adams, 2016). With kelp now being used for alginate production, fertiliser and animal feeds, it is clear that it still remains ecologically, economically and culturally important for society today.

Seaweed drying hut at Freshwater West, Wales from the early 20th century. The seaweed was laid out on the floor for a week, and once dry was sent to Swansea for processing. The use of the huts died out by the 1940s. © Lou Luddington

Despite this significance and longstanding influence on society, kelp forests are not immune to a shifted perspective. Scientific records of UK kelp forests only started in the 1950s (e.g., Crisp and Southward, 1958; Parke, 1948; Walker and Richardson, 1956; Woodward, 1951), yet there are many accounts of maritime kelp exports from the Hebrides, dating back to the 18th century (Argyll Papers). This invaluable wealth of past knowledge remains largely untapped in modern research. To conserve kelp forests for the future and act against a perpetual shifting perspective, it is now more important than ever to look to the past (Thurstan, 2015).

This past knowledge often emerges through a diverse set of alternative sources, written testimony, nautical charts, materials, photographs, popular media, art and more. For example, the historical distribution of kelp has been reconstructed through the use of archival nautical charts (Costa et al., 2020) and by using a combination of historical art, oral histories and other contemporary sources (Selgrath et al., 2024). In combination with modern interdisciplinary research, these sources can detail a holistic, and often fine scale view of the many questions regarding kelp forest change—their past uses, significance to society, distribution, harvesting, and how these perspectives and changes vary through time. With UK kelp forests exhibiting varying degrees of range contractions, abundance changes (Yesson et al., 2015) and generally a lack of historical baseline data (Krumhansl et al., 2016; Smale et al., 2013), there is now an opportunity to better integrate, and collect complementary historical data, to assist on conservation measures for the future.

A freediver explores a modern-day kelp forest in Wales, UK. © Lou Luddington

Understanding historical kelp forests has given researchers in the UK a clearer picture on environmental drivers and kelp forest resilience (Yesson et al., 2015), as well as the vital role they have played in shaping the culture and economy over time (Angus, 2017). In other regions, historical information has enabled the reconstruction of kelp forest habitats, and helped us appreciate their past value to coastal fisheries (Piñeiro-Corbeira et al., 2022). Importantly, historical data has helped to disentangle the differences between long-term natural, and non-natural ecosystem variability in kelp forests (Carnell and Keough, 2019; Reed et al., 2011; Selgrath et al., 2024) and predict its resilience and recovery (Selgrath et al., 2024). These questions are not unique, and they have always been fundamental to deepening our understanding of kelp forests. Looking back can help create a more nuanced understanding of kelp forest change (Lotze and McClenachan, 2013). This is increasingly important for contemporary management, as kelp forests face a range of cumulative stressors—from physical disturbances to the increasing impacts of extreme climatic events.

Historical data continues to prove its value for kelp forests, by extending baselines and providing a picture of the past, yet it does not come without its challenges. Sources of the past are often patchy and discontinuous, but researchers are meeting the challenges with many ways to compensate for the nature of these archives. Within my own research, I work to uncover memories of historical kelp habitats, and I do so by delving into the past with local communities. In the UK, kelp has been a part of the community for many years, providing opportunities for rich and detailed historical accounts of its presence. This approach helps reveal the early interactions, perspectives of change and entangled values of kelp forests and the local community, and provide novel knowledge on a past habitat that is useful for future conservation efforts. In a fast-changing world, it is easy to forget what once was. Now widely recognised across many scientific fields, historical data can contribute to closing knowledge gaps, and help establish more effective protection measures (Thurstan et al., 2015; Thurstan, 2022).

A lot has changed since our journey began with these wonderful forests. Although our interactions with them look different today, our roots remain the same. They continue to play a pivotal role in an ecological, economic, and cultural context, but we also feel a sense of place amongst the kelp-filled coasts of our communities. Focus is shifting back to kelp industries and how we can utilise them for a sustainable future, but we are also enjoying their beauty, recreational use and well-being benefits. So, whilst you read this today, as an article written in time, I hope that you can also spare a thought for the kelp that has gone by, and how it will continue to shape our future.

Share this story

- Ecosystems and habitats

- Ocean of hope

- Threats