Green gravel

Restoring kelp forests, one pebble at a time

MBA research scientist collecting a sample of kelp

6 January 2025

Found along almost a third of the world's coastlines, (Wernberg, 2019) kelp are large brown seaweeds that can form dense forests, similar to jungle or woodland habitats on land. Kelp forests are among the most diverse and productive ecosystems on Earth, contributing to coastal economies with jobs, goods and services. These include providing a habitat for commercially valuable marine species, coastal protection, carbon capture and mopping up nutrient pollution (Eger, 2023).

Kelp forest restoration: A growing movement

Despite their importance, kelp forests are threatened by warming oceans, marine heatwaves, pollution, poor water quality, and overfishing—which can allow kelp-hungry grazers to proliferate. As a result, kelp forests in many areas are shrinking or have been lost, with declines averaging 2% per year globally (Krumhansl, 2016).

As the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030) progresses, kelp restoration lags behind that of forests on land, but is gathering pace (Filbee-Dexter, 2022). An array of techniques are being developed to try and regenerate kelp forests in areas around the world where they have declined or disappeared (Wilding, 2022). These include transplanting kelp from healthy forests, moving fertile kelp material or spores, and excluding or culling grazers such as urchins herbivorous fish. While these methods can be successful, many approaches involve the use of divers, which is costly and labour intensive, making them difficult to scale up (Earp, 2022).

A number of global targets have been set, with almost 200 nations pledging to protect 30% of the world's oceans by 2030 in the Kunming-Montreal biodiversity pact. The Kelp Forest Challenge aims to restore 1 million hectares and protect 4 million hectares by 2040 (Eger, 2024). But meeting these targets is no easy task.

Where the gravel is greener…

To save our shrinking underwater forests, restoration techniques need to be time and cost effective, and easily scalable. “Green gravel” is one such technique, involving growing juvenile kelp on small rocks in aquariums and then planting them out at sea (Fredriksen, 2020). The seeded gravel is ‘planted’ by dropping it over the side of a boat where it sinks, allowing the kelp to attach to the seabed and grow. This is just as effective as hand-deployment by divers and far cheaper (Fredriksen, 2020).

Cat Wilding, marine ecologist and student at Newcastle University in the UK, working on perfecting the 'green gravelling' technique. ©Marine Biological Association

However, challenges remain. For example, storms can wash gravel away before the kelp can attach to wave-exposed shores (Earp, 2024).

As part of an exciting new project in the UK, a team of researchers from The Marine Biological Association (MBA) and Newcastle University are working with the Fishmongers’ Company’s Fisheries Charitable Trust and the Kelp Conservation Initiative to develop the green gravel approach. Different types of stone sourced from around the UK and Europe are being trialled in aquariums to grow native kelp species. To improve the success rate on wave-exposed shores, the team is exploring which size of gravel or pebbles will work best, and testing other materials including tiles and biodegradable twines.

One example is waste scallop shells from the seafood industry. Every year over 30,000 tonnes of shells are sent to landfill—at the industry’s expense. If successful, this technique would provide an alternative use for waste shells, representing a major win for circular economy.

Green gravel: How is it done?

1) Identify healthy adult plants as a donor population.

2) Cut out fertile material from the kelp frond and disinfect it with a quick dip in iodine solution. Leave the parent plant in place to reproduce again next season.

3) Prepare clean gravel substrates in tanks of seawater.

4) Initiate spore release by drying overnight and rehydrating the fertile kelp material. Spread the spore solution between tanks, where spores settle onto the gravel.

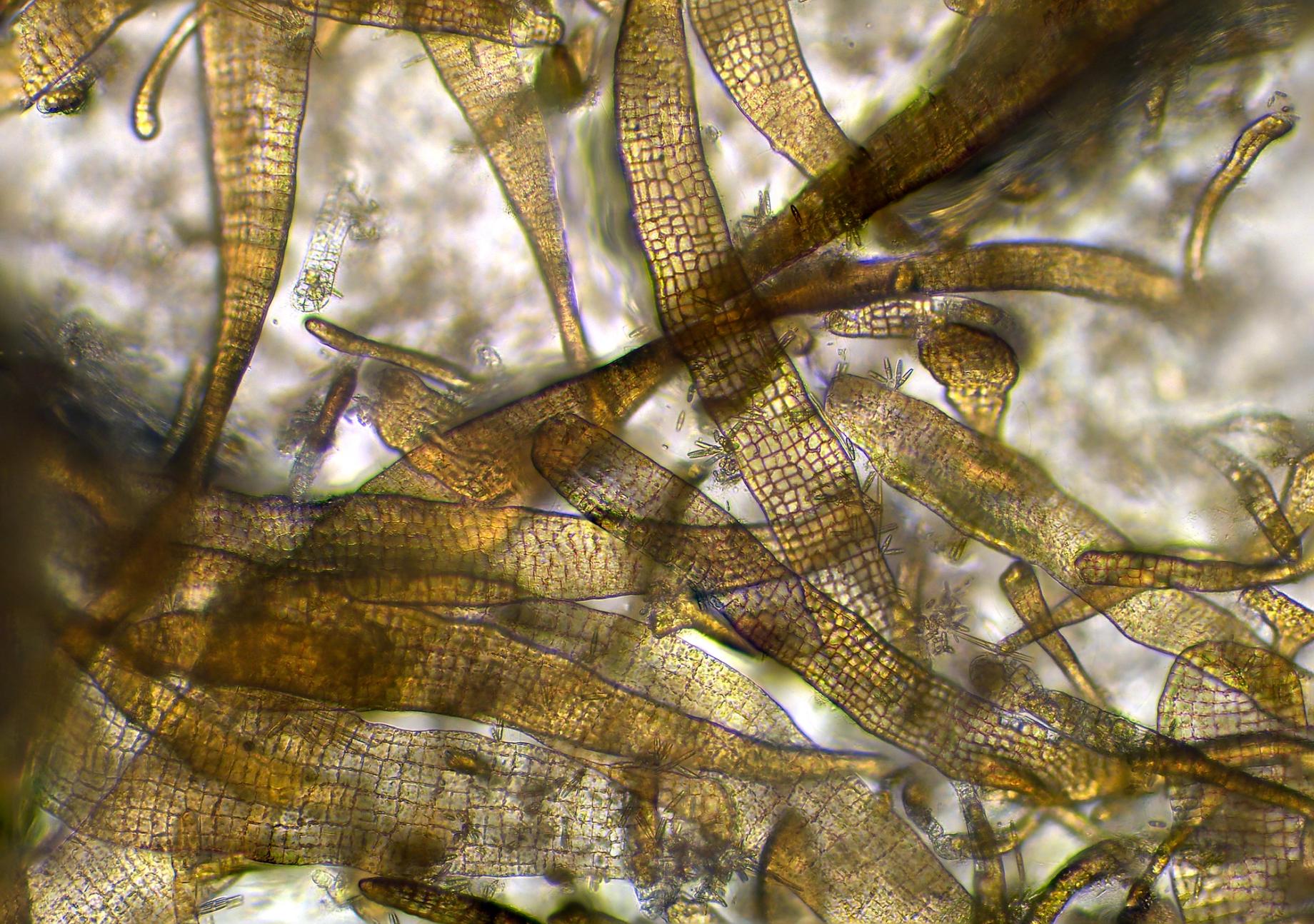

5) Monitor kelp growth. Spores develop quickly, and tiny kelplets are visible as a brown fuzz within 3-4 weeks.

6) After about 3 months (depending on the species), 1cm long kelp will have grown on the gravel. When they are planted at sea, they sink to the sea bed, and develop a larger root-like 'holdfast' attaching them to the gravel.

7) Monitor and measure success to inform future restoration efforts.

The state of kelp in the UK

The rugged coastline of the UK is home to seven kelp species, covering an area of up to 20,000 square kilometres (Yesson, 2015). In general, UK kelp forests appear to be relatively stable (Wilding, 2022) with limited evidence of widespread losses, although local declines have been reported in certain areas, including west Sussex (Williams, 2022). However, the impacts of climate change and human activities mean that losses similar to those witnessed in other regions are a real possibility. The UK team hopes to develop restoration capacity as a precautionary approach, to allow for rapid, targeted action should it be needed in the near future.

The glory of a kelp forest in midsummer conditions © Lou Luddington

The research going on in the UK will contribute to advancing kelp restoration methods through the Green Gravel Action Group. The group has recently identified international challenges and solutions to marine forest restoration, while partners seek to adapt the method to specific locations, for example by testing at different levels of wave energy or gravel texture (Wood, 2024).

Research and development work is still needed. But the simplicity, affordability, and, most importantly, scalability of green gravel methods represent an opportunity to reverse losses of vital kelp ecosystems.

Share this story

- Threats

- People and the sea