This is Reflections

We show. We tell. We inspire.

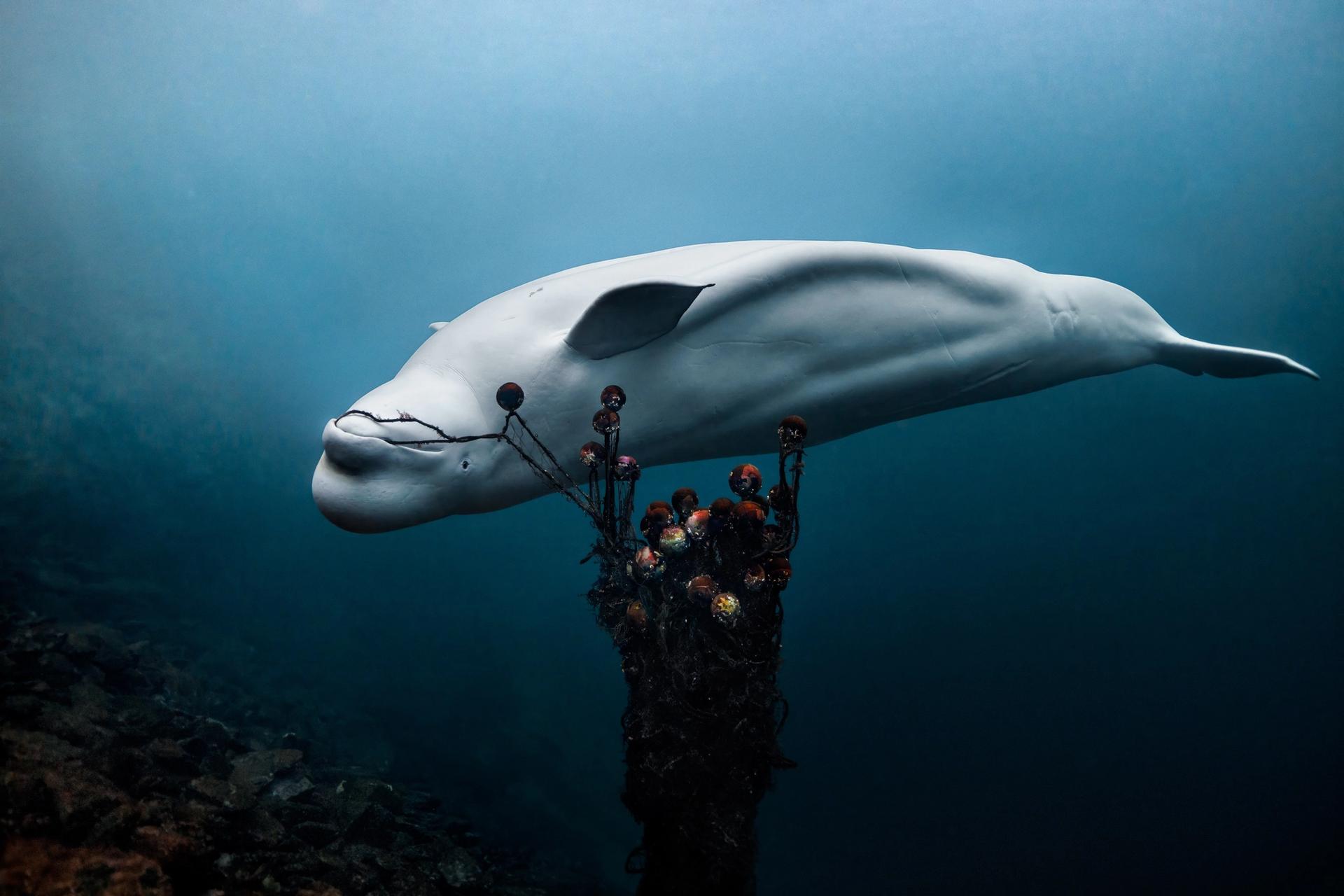

Hvaldimir, the famous Beluga whale suspected of being a Russian spy, behaves in a remarkable manner. He retrieves old fishing nets and other garbage and brings it to humans. His message seems clear: we need to clean this place up. ©Aleksander Nordahl

Nobody needs another shrill reminder that humanity is in the process of killing itself. You already know that dystopic story, and you may also know that the ocean is at the centre of it. That the ocean holds the key to our existence because it has, over billions of years, filled our atmosphere with the oxygen we need to survive, absorbing carbon, and bestowing the earth with abundance. That it stabilises the atmosphere, and mitigates climate change, and even as we have been killing ourselves, the ocean has been keeping us alive. And that if we kill the ocean, we die.

Humans have been dumping their waste in the ocean for so long, that it is common to find symbolic images like this on the seabed. This was seen in the frigid waters of the west coast of Norway.

But we’re not here to sell despair.

It is true that if we talk about the ocean today, there is no escaping the destruction. When our lenses take you below the surface, you will witness the desertified ocean floors, where tens of thousands of square kilometres of flourishing ecosystems have been lost to industrial exploitation and irresponsible human activity. We will follow the science to elucidate how ongoing changes in the ocean spell catastrophe for humanity. But for every danger or tragedy, we find equal measures of awe, inspiration, irony, and wonder.

And we find hope. Because the more we learn about the brilliance and resilience of nature, the more we realise that a prosperous future is a blessing that nature’s forces—especially the ones in the ocean—are conspiring to provide us, if we only let them! That’s a story that needs to be told, and we hope to tell it reliably, and in a way that inspires action.

Reflections was co-founded by a veteran journalist and award-winning photographer, Aleksander Nordahl, who spent decades covering everything from sports to crime to war. But then he realised that humanity’s ultimate battlefront is now the ocean. He was joined by Vanessa Frey, a seasoned investor, entrepreneur and philanthropist with a passion for the ocean. But Reflections is not a pulpit for ocean warriors or conservationists or activists or lobbyists or corporations. It is a platform for factual and authentic visual stories backed by science and propelled by curiosity.

To be authentic means to suspend our judgement, to listen and observe. The keen eyes of our storytellers follow the ocean’s tales through its varied characters. They will take you on board a whaling boat run by a family who has been harvesting the ocean for generations. You will ride the waves with them, and gain the perspectives of the hunter and the hunted, as well as those of scientists of different disciplines and opinions. Reflections’s founder will revisit his days as a journalist in conflict zones, and introduce you to the Somali fishermen-turned pirates. We’ll see how they were pushed into a life of violence after unrestrained industrial fishing emptied Somali waters of fish, leaving an entire population cheated of their traditional livelihood. We suspect he enjoys the irony in the possibility that their presence is helping fish populations recover.

You’ll meet Hartvig Christie, a pioneering scientist who has shaped our understanding of kelp ecosystems, and who, at the age of 76, can hardly be restrained from diving into the icy waters of the Norwegian Sea. (Or from his appetite for good food and Nordic liquors, for that matter.) In significant pain, just weeks before a hip replacement surgery, he’s still diving. Having dedicated his life to kelp forests, he says he cannot stop diving and continuing his research, because he must stand by younger entrepreneurs who are at last seeing some success in restoration efforts.

Hartvig, a.k.a. “kelp father”, joins us as our scientist-in-residence as we launch Reflections with a series of articles on blue forests. These vibrant ecosystems create and support an astonishing diversity of life, pump out oxygen, create food, resources and livelihoods, protect our coastlines and stabilise our climate. We cannot do without blue forests. And yet, nobody seems to be talking about how quickly we are losing them.

Together with our in-house scientists and storytellers, Hartvig will follow the kelp forest “game of thrones” between humans, fish, crabs and urchins; revealing how sea urchins came to be the reigning terrors of so many modern-day kelp forests, their natural predators having been fished to oblivion. He will also delve into the lives and habitats of dozens of other species that thrive in kelp forests.

Hartvig says people are too caught up with the capacity of blue forests to sequester carbon. Blue forests bind vast amounts of carbon when they grow—much more than what terrestrial forests would. Once they have grown to their maximum density, they stop bonding as much carbon. But they continue to yield immense economic benefits—as much as €16.7 million per year for each square kilometre, according to a research project he participated in (Verbeek et al., 2021). This includes fish and other commercially important marine species, and many other direct and indirect services. To put things into perspective, 5,000 sq. km of Norway’s kelp forests are currently overrun by urchins. That’s a value of €83.6 billion a year by that calculation.

The notion is only theoretical. Much more work needs to be done to understand the economic value of blue forest ecosystems. But it is an idea that supports our vision of a healthy and abundant ocean.

We will also immerse you in the poetic beauty of blue forest ecosystems—like the magical and ancient climate hero that few know about: maerl. And, as we probe the disappearance of kelp cover in so many places, we will also follow the discovery of mysterious deep-water kelp forests off the coast of Mozambique. How is it possible that this finicky seaweed that longs for shallow, chilly water, and plenty of sunlight, is thriving 30 metres below the surface of these tropical waters? If they exist here, where else do they exist that we haven’t even looked? And what does this mean for the prospects of kelp restoration?

Our lifeline on the line

For hundreds of years the ocean has shown enormous resilience, absorbing vast amounts of carbon dioxide, heat and toxins, buffering a relentless onslaught of human stresses to maintain equilibrium. But planet-wide oceanic systems are collapsing. In 2024, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission’s State of the Oceans report found that 20-35 % of blue forest ecosystems have already been lost since the 1970s. Global warming is raising sea levels, altering ocean currents (Gulev et al., 2021) and storm tracks. Together with ocean acidification and deoxygenation, it is causing dramatic biodiversity loss, population extinction, coral bleaching, infectious diseases and changes in animal behaviour. Greenland is losing an average of 30 million tonnes of ice an hour which could trigger a collapse of ocean currents in the north Atlantic (Greene et al., 2024). Meanwhile, 170 trillion plastic particles are floating in the ocean (Persson et al., 2022)—that's a thousand times the number of stars in our galaxy.

After the opening series on blue forests, we will move on to each of these threats to the ocean. We will talk about the ocean’s mammals, including whales and dolphins, ocean pollution and exploitation, the impacts of commercial fishing, fish farming, shipping and mining. We will talk about efforts to mitigate these threats, including marine protected areas and conservation initiatives. And we will talk about hope.

Much is lost to human greed, but not all humans are lost to greed. We will seek inspiration from a couple in the United Arab Emirates, who are combating the prohibitive cost of climate tech by building alternatives in their backyard, and sharing it across the world. Their business model benefits communities, and multiplies the impact of the technology they create, while remaining profitable. Could it be an answer to the difficulty developing countries face in procuring green tech?

Through this story and others like it, Reflections will seek out possible solutions to crises in the ocean. In our blue forest series we look at how kelp is harvested in Gaansbai, South Africa, with an effort to keep it sustainable. We will contrast that with industrial kelp trawling in Norway. We will publish stories from academics, experts and people on the ground all over the world. Aaron Eger, for example, tells us about the state of Australia’s Great Southern Reef, and Cat Wilding and Hannah Earp share their successes with green gravelling, a novel technique for restoring kelp forests.

It isn’t easy to be optimistic about the world today. But with these and countless other videos and articles about the oceans, we are launching a platform for stories that evoke and provoke you. We show and then we tell. From all parts of the world, we bring ideas and images that make readers reflect. And eventually, inspire them to act. We also invite you to share your stories—the good, bad and the ugly—and to tell them with regard for facts and science. You will find a tab on our website called “your stories”, where we will publish stories from our readers.

“I feel like I’m at the most important press conference of my life, and I’m the only journalist there,” says Aleksander. The importance of the ocean is severely understated—because it isn’t as easy to see as what is happening in the Amazon. “The narrative cannot be controlled by activists, corporations, governments, lobbyists or any interested party,” he says. “The narrative must be driven by visual evidence and curiosity, and based in facts and science.” In other words, our only allegiance is to the truth.

“The ocean, in my point of view, offers the biggest leverage we've got to bring about change,” says Vanessa. “It gives us efficient ways to solve today’s problems, if we can learn more about it. I envision Reflections as a dynamic platform addressing global oceanic issues in a way that is accessible to a diverse audience—from fishermen to scientists, and especially the wider public.”

Vanessa and Aleksander joined hands in earnest in early 2024 to put together Reflections. Our team has been working fervently for months to put together this platform. It is scarcely ready, but there is no time to wait. These stories need to see daylight. The mission is urgent. And we invite you to join us as we dive in.

Share this story

- Threats

- Ocean of hope